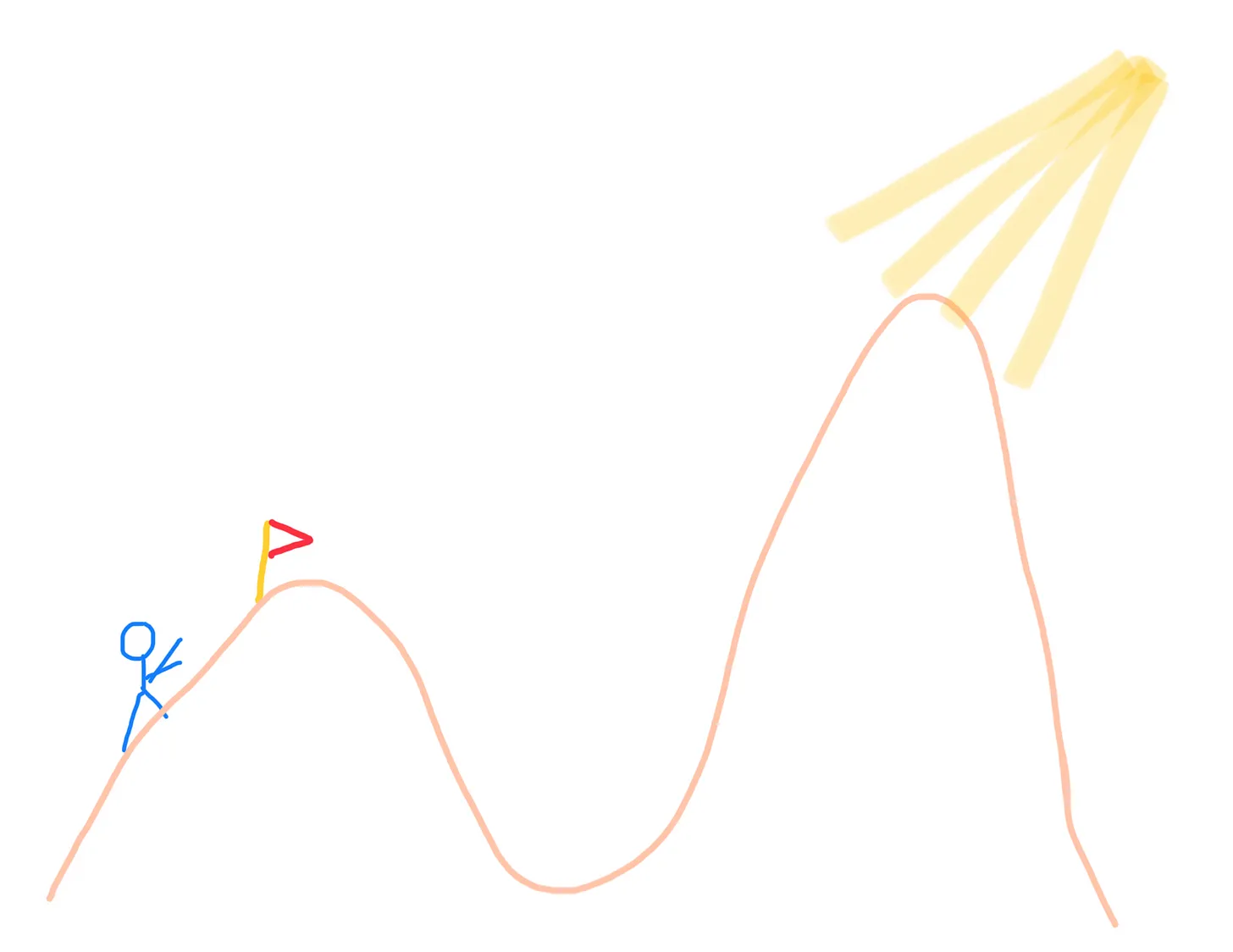

Local and Global Maxima

When making design decisions, we should stay aware of whether we’re pursuing a local maximum or a global maximum.

Think of a project you’re working on that involves some tricky decisions. Now visualize that project as a mountain, with the summit being the ideal version of that project — the version that best accomplishes the stated goals.

As we tweak our design, we move higher up the mountain. Find a font that performs slightly better than the other choices? Move up. Change some wording in response to an A/B test? Move even higher. Swap some buttons to better suit user data? Move higher still.

Here’s the problem on relying only on data and experiments to make design decisions. Yes, our metrics keep getting better as we optimize our design, but we don’t know if we’re climbing the right mountain. Maybe we’re still in the foothills, and the version that really accomplishes our goals best has a different starting point entirely.

Here’s a terrible drawing I did on my iPad, after discovering that my Apple Pencil is no longer working:

I’m not disparaging A/B testing and other statistical techniques — they’re extremely valuable, if we’re confident about the direction we’re going. They help us choose between options that already exist, and so they’re useful for helping us find a version that’s better rather than unearthing the version that’s best. They can help us summit the mountain we already know about, but not find a whole new mountain.

“Now wait,” you may be saying. “Why not test between different directions entirely?”

Yes, that’s true. But it still relies on us having already come up with the options we’re choosing between — it can help us decide, but not create. A real sea change requires the kind of creative leap that’s harder to systematize, and impossible to force with research alone.

But more on that next time.